True Katydid

The nighttime chorus of insects that started in late July or August and continues through September with increasing intensity is one of those things that people either love or hate. I fall squarely in the first category; like many people, for me the sounds are synonymous with warm late-summer nights. As far as I’m concerned, there’s no better way to fall asleep than next to an open window with the sounds of the night insects pouring in. My wife, however, is one of those people in the other category: for her the insect chorus, while something she’ll admit can be pleasant sounding, is more importantly something that keeps her awake. So our bedroom window stays firmly shut this time of year.

While insects produce a great many sounds for a wide range of reasons, our late summer nights are filled with very purposeful sound. The chorus we hear consists primarily of true “songs” in the biological sense that they’re produced to attract mates. And there are only three major groups of insects that produce such songs: crickets, katydids and cicadas, all members of an insect order known as the orthopterans. And for our purposes here (describing the nighttime sounds) cicadas can be left out of this discussion: they do their singing in broad daylight, usually at the hottest time of the day.

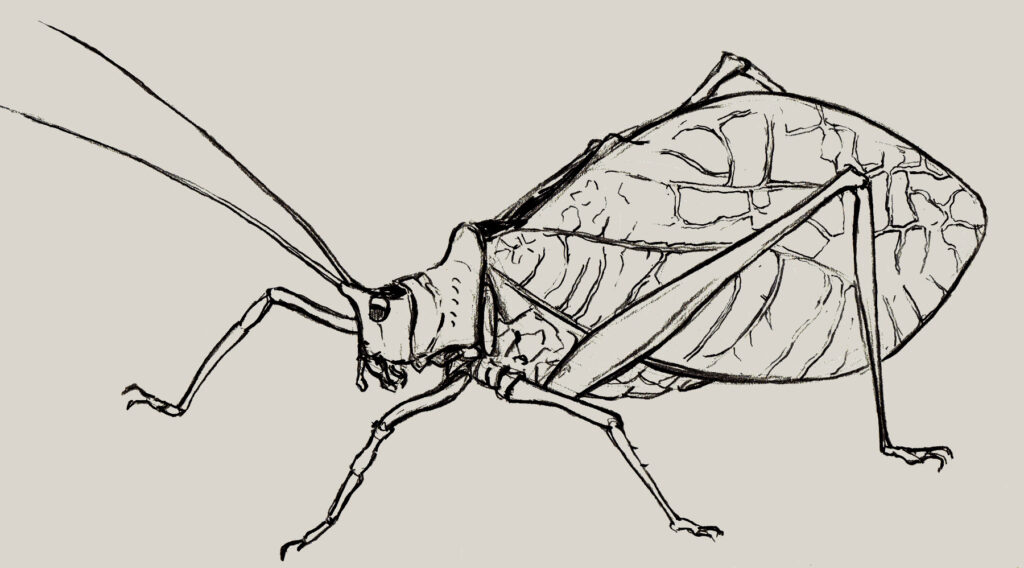

A True Katydid the author encountered on a sidewalk, likely washed out of a nearby tree during a storm.

So, our cacophony of nighttime sound primarily boils down to two main stars (or culprits, depending on your perspective): crickets and katydids. In general, it’s the crickets that produce the soft, chirping background sound; katydids are responsible for the loud, raspy (some might say more annoying) sounds we hear in the foreground (there are also many insect songs that are beyond our capacity to enjoy, either because the volume of their songs is too low or the pitch too high). There are thousands of cricket species across the world, but we’re generally hearing several species of field and tree crickets. Similarly there are thousands of species of katydids across the world and several that can be heard on Long Island, but we mostly hear the species known as the “true katydid” (pictured here).

The katydid’s name, of course, derives from its song, “KAY-TI-DID” a moniker given by early American settlers after arriving in North America (to what must have been an incredible nighttime serenade!). However, if you spend a little time listening you’ll notice that the katydid’s song is much more varied, often including more than just three quick notes and often ranging in pitch and volume. With a little creativity, you can imagine the insect outside your window is saying just about anything. “Go to bed” is one appropriate instruction people often say they hear.

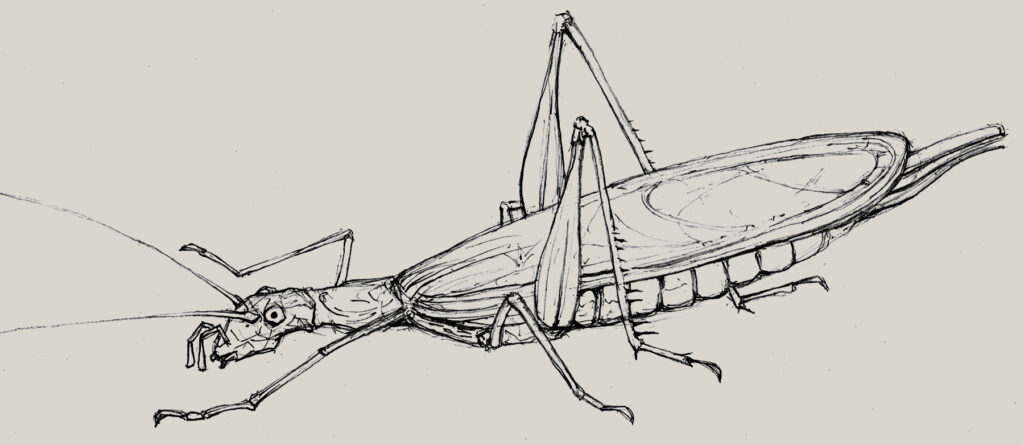

Four-spotted Cricket

Four-spotted Cricket

Another is what many people refer to the annual summer debate about whether Katy “did” or “didn’t.” The argument can seem endless once you start to listen: “Katy did, Katy didn’t, yes she did, no she didn’t,” and on an on. One careful observer, Long Island naturalist and author Edwin Way Teal, noted that by the time the season winds down there is a resolution to the debate. With colder weather slowing the katydids down and forcing them to produce fewer sounds, they more often limit their calls to just two or three quick notes instead of carrying on. The answer becomes clear: Katy did. At least, that is, until the debate picks up again the following summer!

One thing you may notice is that the raspy song of the katydid is more prominent when you’re on higher floors (perhaps in your bedroom trying to fall asleep!). That’s because, where crickets can be found in trees, bushes or even on the ground (depending on the species and conditions), katydids stick to the treetops. They’re usually in the very top of the tree canopy, often in the tallest oaks, where their leaf-like appearance camouflages them incredibly well. In fact, they’re much easier to hear than to see. For all the katydids I’ve heard and enjoyed over the years, I’ve only seen a few in my lifetime (including the one pictured here that I once found on the sidewalk during a rainstorm).

Another thing that’s puzzled me is why the evening chorus of insects was so late in arriving each year. The sound often seems a summer memory, and I sometimes find myself listening for them in June or July. The truth is, they’re still growing up. After hatching in the spring, katydids and crickets need several months to grow, molt and mature to the point that they’re ready to start mating. In our region, this usually happens, depending on the weather conditions, in early August.

One common misconception is that these singing insects produce their song by rubbing their legs together. How many times have we seen images of a cartoon cricket playing the fiddle with its leg? While there are some species of grasshopper that rub their legs together to produce sound (which is often very soft, and sometimes imperceptible to the human ear), the fact is both crickets and katydids produce their songs by rubbing their forewings together (most species have two sets of wings). The hard edge of one wing is rubbed against special ridges on the other wing to make the sound; the wing membrane itself acts as an amplifier. The process is often described as similar to dragging your finger along the teeth of a comb.

As September turns to October and the temperature drops, the song of the summer insects will gradually slow. When the mercury hits 50° it is said it will all be over. Before it ends, there’s a perceptible lowering of the tempo, frequency and volume. I always find a bit of sadness in this somber end to the insect chorus, this last attempt to mate. But I take solace in the fact that many crickets and katydids have been heard; they have mated successfully and deposited eggs in the bark of trees to await the warmth of spring when the cycle can begin anew. Enjoy what’s left of this year’s serenade and know that come next summer, the chorus will return.