Take time in life to smell the rabbits, eat the flowers, and pet the cactus.

– Fortune Cookie Aphorism

As long as I can remember, I have always been attracted to cacti. I believe I imprinted on these bizarre plants during the accumulated hours of spellbound time passed as a kid in darkened movie theaters, transfixed by the endless procession of desert-strewn cowboy-and-Indian

Technicolor westerns. My fixation certainly didn’t come from actually wandering in any of those great American deserts.

I grew up in Manhattan, and I didn’t see any real desert denizens until I was 18 years old. This momentous day probably occurred when I first encountered the splendidly deranged creativity of “natural selection” as revealed in neatly arranged terracotta pots in a bewildering display of spiny succulents at the local F.W. Woolworth Five and Dime. I now find that I am driven by a fundamental need to collect these plants and arrange them, for visual contemplation and pleasure, on any sunny windowsill available. I currently have 18 flowerpots containing 30 individual plants perched on the western-facing sill in my living room. The cacti range from less than an inch high to one specimen that is over 4 feet tall and growing. My dream is to win the lottery and build a sunroom on my deck, or just replace the entire deck with a greenhouse to allow a serious expansion into this prickly, fascinating world.

Life on our planet began about 3.6 billion years ago, and it is said to have all started in water. Life is strange (look it up), and approximately 3.55 to 3.57 billion years later, the ancestral “cactus” started to evolve a number of admirable adaptations necessary to compete for resources in the demanding desert environment. Over the passing eons the broad green ancestral leaves—fit for cooler, damper climates by allowing for the transpiration of water and exchange of gases during the day—mutated into narrow, stiff, sharply pointed spines that dramatically reduced the loss of precious fluids and, simultaneously, protected their succulent bodies from predation by hungry and thirsty desert foragers. Unlike the majority of leafy plants in more forgivingly humid habitats, the stomata of the cactus (the open pores on the underside of leaves) are found within their stems, and they are sealed during the day to prevent evaporation in the extreme heat. The stomata open during the cool of the desert night, when they take in carbon dioxide and store it away for later use during the day in a special photosynthetic process that provides for slow nourishment and growth.

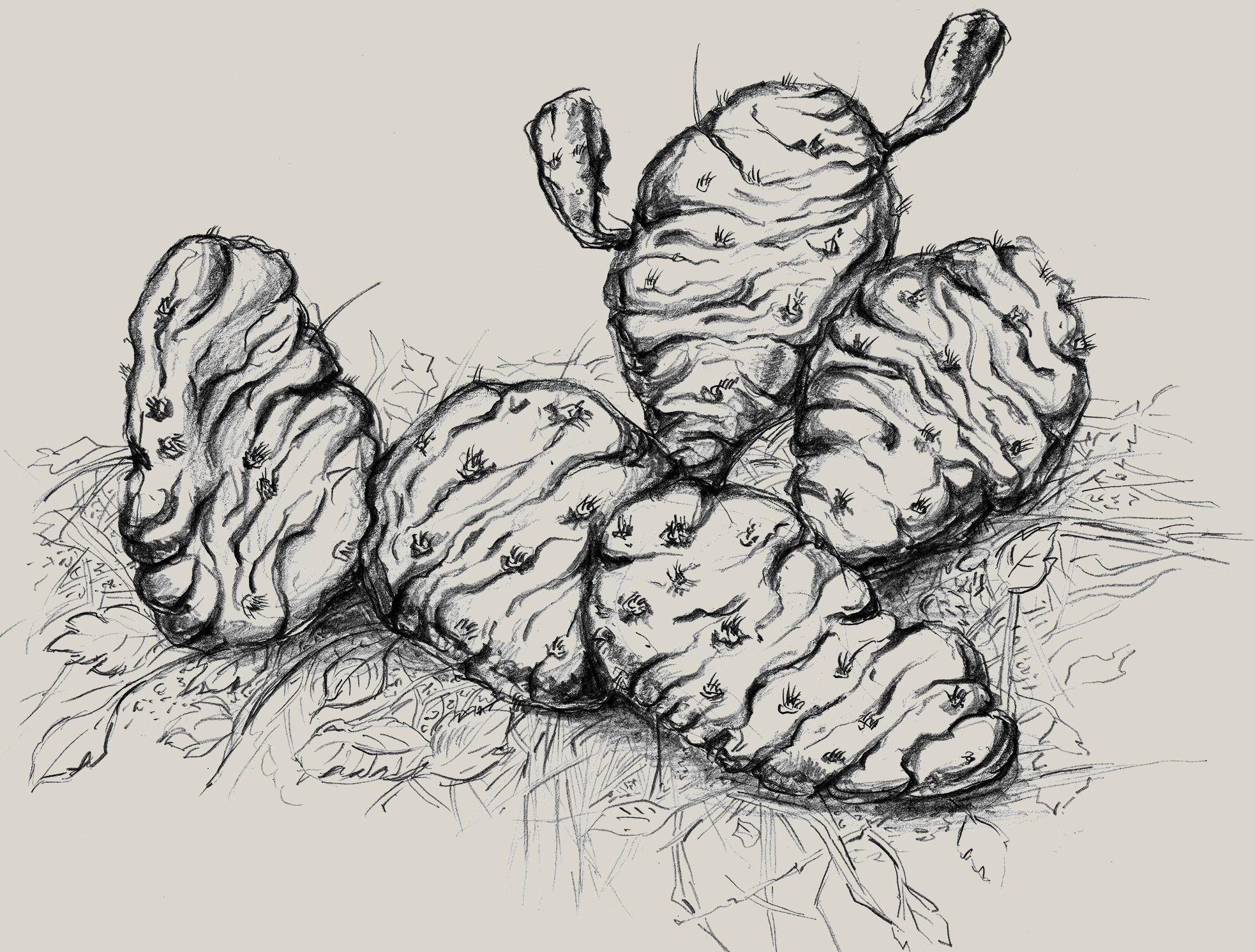

The succulent, engorged, green bodies of cacti, which some might mistake (especially in those cacti with pad-like structures) for swollen leaves, are the stems of these stoic survivors. Typically, these stems are covered with a waxy cuticle that helps them retain any moisture they are able to avariciously hoard within those protecting walls. The ratio of surface area to volume is low, which also helps retard evaporation of liquid. It is a wonder to ponder that such a self-contained, slow-growing, miserly plant should put forth such profligate floral displays that annually blaze forth under fierce sunlight, amid rippling waves of sand, all in an arid and hostile ocean of hot air.

Ok, perhaps you’re scratching your head by now and wondering, “Why is he going on and on about deserts and cacti. Isn’t “Field Notes” supposed to deal with natural life on Long Island? After all, it regularly rains here, we have lakes, ponds, creeks, and rivers, and the island sits beside a surging ocean of water. Cactus?” Ok, true enough, but I invite you to visit my house in February and trudge through my snow-laden lawn to peer at the ground beneath my bedroom windows—the dark green sight peeping up at you through the frigid white blanket is the “Eastern Prickly Pear Cactus” (Opuntia humifusa), a true native of Long Island!

Although many Opuntia species are found in deserts in places such as Texas, New Mexico, and old Mexico, O. humifusa’s range does not typically include true deserts. The eastern prickly pear cactus has wandered backward, a bit closer to its ancestral origins. Even though it continues to share the arid adaptations of its desert-dwelling cousins, all geared up for the storing and conservancy of water, it has also adapted to life in the winter. Around November, its appearance becomes somewhat prune-like as it reacts to the steadily dropping temperatures by draining water from its cells. Now that is a strange adaptation—a cactus purposely losing water. The combination of internal water and freezing temperatures results in ice crystals, and those crystals can easily damage the cell walls. This adaptive loss of liquid also deflates the pads and causes this plant to lay low and out of the way of the wintry blasts that visit Long Island from time to time. But let us leave these frigid thoughts of February and fast-forward to June.

Ahh, June—the month when this shriveled, shivering, prostrate sufferer, pathetically hugging the earth, transforms from a crazy-quilt patch of cactus pads swelling in the brilliant sunshine, warm air, and spring rains into a fully fleshed-out jumble of fresh green rising, bursting with all that “juice and joy” so exuberantly celebrated by the English poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins. Soon, upon these branching pads of springtime green erupt large yellow blooms frequently attended by tiny winged jewels—virescent green metallic bees (Agapostemon virescens) searching for sips of sweet nectar, their frenzied feeding causing the crowd of delicate pollen laden stamens to swoon toward the patient pistil. This tableau of beauty and busyness is set against a bed of carmine lying deep within the very heart of the blossom. But flowers do not last forever, and O. humifusa’s petals eventually fade to a paler shade, shrivel, and drop to the ground. In time, small fruits full of seeds generate from the fertilized flowers, and they begin life sporting a green color that, over time, morphs into a reddish-purple. The fruits are tubular, narrow at the base and swelling gently to a flat, abrupt, and slightly concave surface at the top. They seem incongruous, even somewhat comical, as they sit, here and there, balanced at odd angles upon the chaotic pads’ edges.

Glochids! I am sure you know of cactus spines, for they are legendary—they are nearly the very essence of the plant in the common imagination, and the eastern prickly pear does grow them…. I can deal with spines; they are large and noticeable, and easily avoidable. It’s the glochids that get me. Glochids are tiny bundles of barbed bristles grouped and protruding from numerous areoles (tiny craters in the cactus skin), and they dot the flat surfaces and edges of the pads and fruits. Do not even think of touching this plant with bare hands, and be warned that cloth gloves will not suffice, for the softest touch will break off the glochids, which will doggedly migrate through the fabric and into your skin. You will then be spending much tweezering time plucking free these minute, annoying spears. As an experienced, and chastened, lover of Opuntia humifusa, I heartily recommend the wearing of leather gardening gloves.

The eastern prickly pear cactus flourishes in Montana, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and virtually all states in between, plus in southern and western Canada. But you don’t have to journey to such far-off and exotic places to become acquainted with O. humifusa. These delightful plants can be found year-round, for example, at Target Rock National Wildlife Refuge, Caumsett State Historic Park, and Orient Point—and even in Islip in the native plant gardens Seatuck volunteers maintain at the Scully Estate. So, by all means avoid the glochids, but do not fail to embrace the eons-old beauty of this most unexpected native that thrives upon our water-anchored island

Take time in life to smell the rabbits, eat the flowers, and pet the cactus.

– Fortune Cookie Aphorism

As long as I can remember, I have always been attracted to cacti. I believe I imprinted on these bizarre plants during the accumulated hours of spellbound time passed as a kid in darkened movie theaters, transfixed by the endless procession of desert-strewn cowboy-and-Indian Technicolor westerns. My fixation certainly didn’t come from actually wandering in any of those great American deserts.

I grew up in Manhattan, and I didn’t see any real desert denizens until I was 18 years old. This momentous day probably occurred when I first encountered the splendidly deranged creativity of “natural selection” as revealed in neatly arranged terracotta pots in a bewildering display of spiny succulents at the local F.W. Woolworth Five and Dime. I now find that I am driven by a fundamental need to collect these plants and arrange them, for visual contemplation and pleasure, on any sunny windowsill available. I currently have 18 flowerpots containing 30 individual plants perched on the western-facing sill in my living room. The cacti range from less than an inch high to one specimen that is over 4 feet tall and growing. My dream is to win the lottery and build a sunroom on my deck, or just replace the entire deck with a greenhouse to allow a serious expansion into this prickly, fascinating world.

Life on our planet began about 3.6 billion years ago, and it is said to have all started in water. Life is strange (look it up), and approximately 3.55 to 3.57 billion years later, the ancestral “cactus” started to evolve a number of admirable adaptations necessary to compete for resources in the demanding desert environment. Over the passing eons the broad green ancestral leaves—fit for cooler, damper climates by allowing for the transpiration of water and exchange of gases during the day—mutated into narrow, stiff, sharply pointed spines that dramatically reduced the loss of precious fluids and, simultaneously, protected their succulent bodies from predation by hungry and thirsty desert foragers. Unlike the majority of leafy plants in more forgivingly humid habitats, the stomata of the cactus (the open pores on the underside of leaves) are found within their stems, and they are sealed during the day to prevent evaporation in the extreme heat. The stomata open during the cool of the desert night, when they take in carbon dioxide and store it away for later use during the day in a special photosynthetic process that provides for slow nourishment and growth.

The succulent, engorged, green bodies of cacti, which some might mistake (especially in those cacti with pad-like structures) for swollen leaves, are the stems of these stoic survivors. Typically, these stems are covered with a waxy cuticle that helps them retain any moisture they are able to avariciously hoard within those protecting walls. The ratio of surface area to volume is low, which also helps retard evaporation of liquid. It is a wonder to ponder that such a self-contained, slow-growing, miserly plant should put forth such profligate floral displays that annually blaze forth under fierce sunlight, amid rippling waves of sand, all in an arid and hostile ocean of hot air.

Ok, perhaps you’re scratching your head by now and wondering, “Why is he going on and on about deserts and cacti. Isn’t “Field Notes” supposed to deal with natural life on Long Island? After all, it regularly rains here, we have lakes, ponds, creeks, and rivers, and the island sits beside a surging ocean of water. Cactus?” Ok, true enough, but I invite you to visit my house in February and trudge through my snow-laden lawn to peer at the ground beneath my bedroom windows—the dark green sight peeping up at you through the frigid white blanket is the “Eastern Prickly Pear Cactus” (Opuntia humifusa), a true native of Long Island!

Although many Opuntia species are found in deserts in places such as Texas, New Mexico, and old Mexico, O. humifusa’s range does not typically include true deserts. The eastern prickly pear cactus has wandered backward, a bit closer to its ancestral origins. Even though it continues to share the arid adaptations of its desert-dwelling cousins, all geared up for the storing and conservancy of water, it has also adapted to life in the winter. Around November, its appearance becomes somewhat prune-like as it reacts to the steadily dropping temperatures by draining water from its cells. Now that is a strange adaptation—a cactus purposely losing water. The combination of internal water and freezing temperatures results in ice crystals, and those crystals can easily damage the cell walls. This adaptive loss of liquid also deflates the pads and causes this plant to lay low and out of the way of the wintry blasts that visit Long Island from time to time. But let us leave these frigid thoughts of February and fast-forward to June.

Ahh, June—the month when this shriveled, shivering, prostrate sufferer, pathetically hugging the earth, transforms from a crazy-quilt patch of cactus pads swelling in the brilliant sunshine, warm air, and spring rains into a fully fleshed-out jumble of fresh green rising, bursting with all that “juice and joy” so exuberantly celebrated by the English poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins. Soon, upon these branching pads of springtime green erupt large yellow blooms frequently attended by tiny winged jewels—virescent green metallic bees (Agapostemon virescens) searching for sips of sweet nectar, their frenzied feeding causing the crowd of delicate pollen laden stamens to swoon toward the patient pistil. This tableau of beauty and busyness is set against a bed of carmine lying deep within the very heart of the blossom. But flowers do not last forever, and O. humifusa’s petals eventually fade to a paler shade, shrivel, and drop to the ground. In time, small fruits full of seeds generate from the fertilized flowers, and they begin life sporting a green color that, over time, morphs into a reddish-purple. The fruits are tubular, narrow at the base and swelling gently to a flat, abrupt, and slightly concave surface at the top. They seem incongruous, even somewhat comical, as they sit, here and there, balanced at odd angles upon the chaotic pads’ edges.

Glochids! I am sure you know of cactus spines, for they are legendary—they are nearly the very essence of the plant in the common imagination, and the eastern prickly pear does grow them…. I can deal with spines; they are large and noticeable, and easily avoidable. It’s the glochids that get me. Glochids are tiny bundles of barbed bristles grouped and protruding from numerous areoles (tiny craters in the cactus skin), and they dot the flat surfaces and edges of the pads and fruits. Do not even think of touching this plant with bare hands, and be warned that cloth gloves will not suffice, for the softest touch will break off the glochids, which will doggedly migrate through the fabric and into your skin. You will then be spending much tweezering time plucking free these minute, annoying spears. As an experienced, and chastened, lover of Opuntia humifusa, I heartily recommend the wearing of leather gardening gloves.

The eastern prickly pear cactus flourishes in Montana, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and virtually all states in between, plus in southern and western Canada. But you don’t have to journey to such far-off and exotic places to become acquainted with O. humifusa. These delightful plants can be found year-round, for example, at Target Rock National Wildlife Refuge, Caumsett State Historic Park, and Orient Point—and even in Islip in the native plant gardens Seatuck volunteers maintain at the Scully Estate. So, by all means avoid the glochids, but do not fail to embrace the eons-old beauty of this most unexpected native that thrives upon our water-anchored island